Dimostriamo che √2 è irrazionale usando 6 dimostrazioni diverse.

1° Proof:

Suppose that √2 ∈ ℚ then there exist two coprime integers a and b such that √2=a/b. It follows that 2b²=a². So a² is even, that is, a is even, or a=2k with k being an integer. But then 2b²=4k², or b²=2k², from which b is even, which is absurd since a and b were supposed to be coprime.

2° Proof:

If √2 ∈ℚ then this number is fixed by every element of Gal(ℚ(√2)/ℚ) which is false since the ℚ-automorphism σ:ℚ(√2)—>ℚ(√2) defined by σ(a+b√2)=a-b√2 does not fix √2. ■

3° Proof:

This proof is attributed to John Conway rewritten by Daniele Bjorn Malesani:

1) Let k be the largest integer less than √2 (well, obviously k = 1!). We then have 0 < √2 – k < 1.

2) Let us consider the sequence a(n) = (√2-k)ⁿ, which naturally tends to 0 as n → +∞ because it is a power with a base between 0 and 1.

3) Let us explicitly calculate some terms of a(n):

- a(1) = √2 – 1;

- a(2) = (√2-1)·a(1) = (√2-1)·(√2-1) = 3 – 2√2;

- a(3) = (√2-1)·a(2) = (√2-1)·(3-2√2) = 5√2 – 7;

- a(4) = (√2-1)·a(3) = (√2-1)·(5√2 – 7) = 17 – 12√2;

- etc …

It is easy to see that in general a(n) = x(n) √2 + y(n), where x(n) and y(n) are suitable integers (we are not interested in their exact value). If desired, a formal proof can be obtained by induction.

4) Now suppose by contradiction that √2 is rational, so √2 = p/q (with p, q positive integers). We will then have:

a(n) = x(n) p/q + y(n) = [x(n) p+q y(n)] / q = z(n) / q,

where z(n) = x(n) p+q y(n) is some positive integer. Whatever its value, naturally z(n) ≥ 1, and therefore: a(n) ≥ 1/q > 0.

5) And here we have reached an absurdity, because a(n) → 0 as n → +∞, so, from a certain n onwards, a(n) must be less than 1/q ■

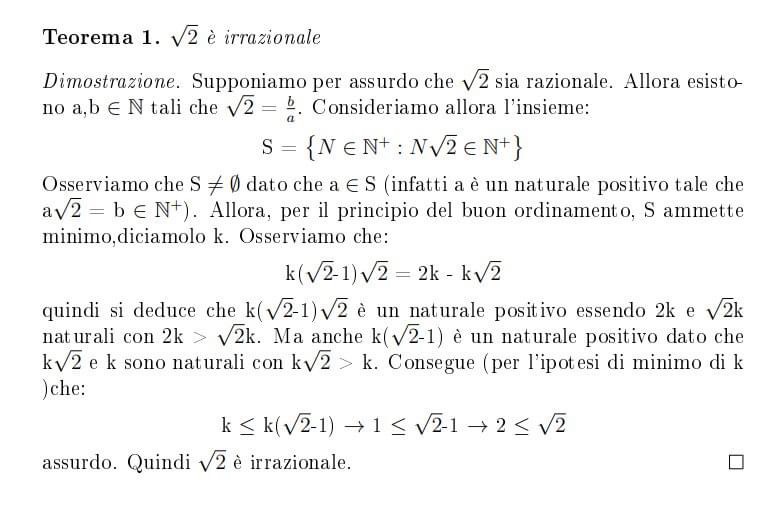

4° Proof:

This essentially uses the principle of good order in a clever way.:

5° Proof:

The polynomial X²-2 is irreducible on ℚ[X] by the Eisenstein criterion so it has no roots in ℚ, i.e. √2 ∉ ℚ. ■

6° Proof:

The polynomial X²-2 has no rational roots by the rational roots theorem, so √2 ∉ ℚ. ■

Leave a comment