Numbers are awesome.

Here’s why.

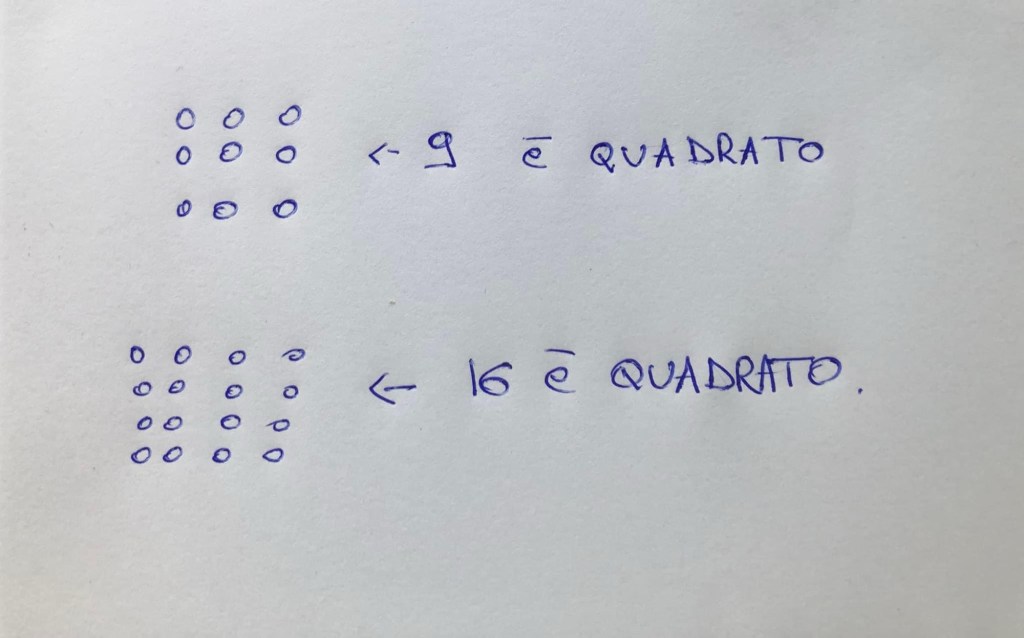

Yesterday I made a video about the so-called “n-gonal numbers”. I’ll explain what they are as we go. Let’s start by saying that a natural number k is said to be “square” if k=n² for some natural number n. This definition, which is now completely algebraic, was given in the first centuries BC in a completely different way. It was said: a natural number k is square if with k units (for example some dots) I can construct a square. For example, by making a drawing you can see that 9 is square, as is 16 (see the figure below)

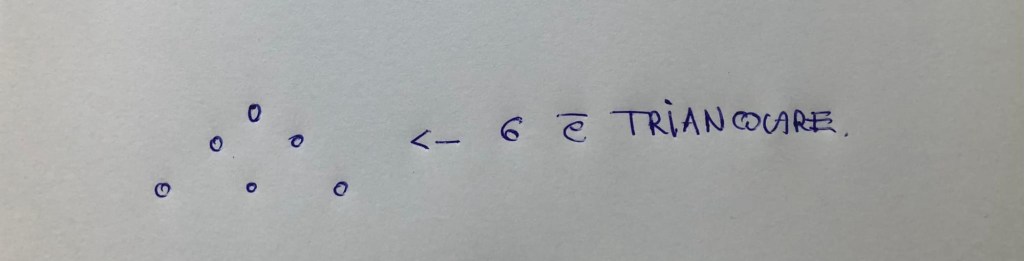

Clearly the visual definition that was given in the past coincides with the more modern algebraic one. Now we know well that not only squares exist but also other geometric figures, such as triangles. So we can give another definition: a natural number k is called an n-th triangular number if it has the form n(n+1)/2:=Tn. This too was given in a completely different way. It was said that a natural number k is triangular if with k dots I can form an isosceles triangle. It is immediately clear that k=6 is triangular (see photo).

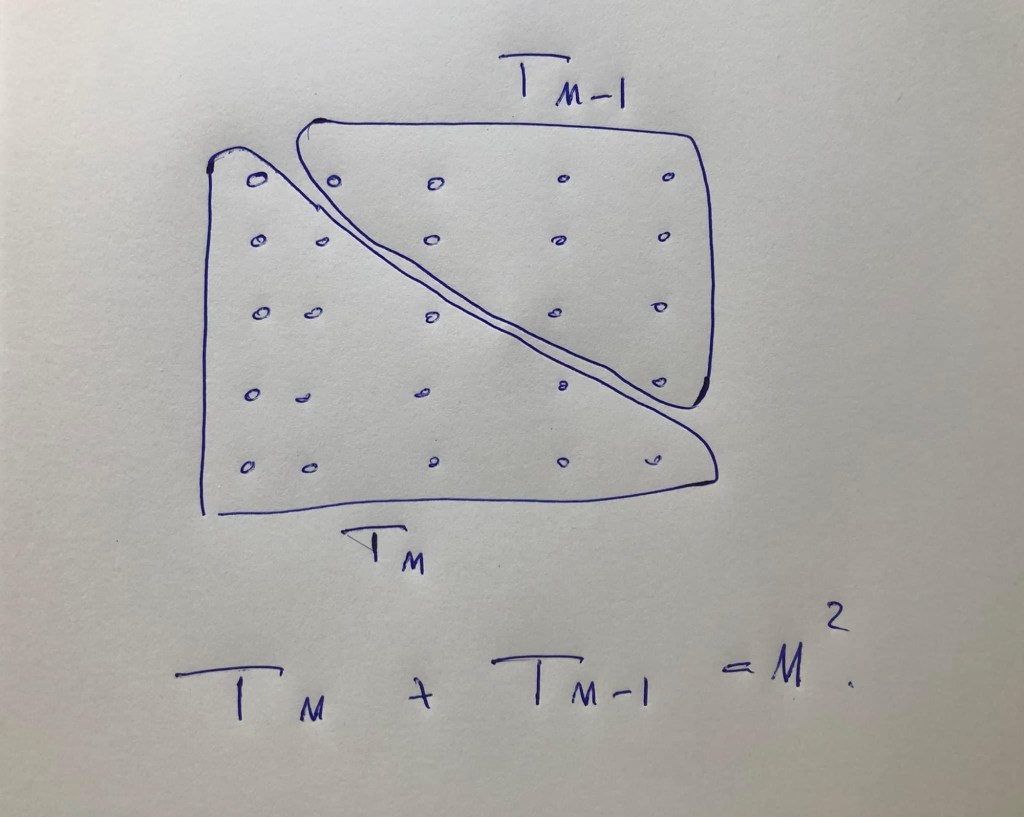

Clearly the visual definition coincides with the algebraic definition of now. Theon of Smyrna, in the 4th century BC, demonstrated the first relationship between square and triangular numbers: “every square is the sum of two triangular numbers”. The demonstration, although trivial since it is enough to observe that n²=Tn+T(n-1), can be done by observing that any square with n² units can always be divided into two triangles with Tn and T(n-1) units (see the figure).

Of course, it doesn’t stop there. Gauss, on July 19, 1796, wrote the following statement in his diary: “Every positive integer is the sum of 3 triangular numbers”. The demonstration of this fact, again by Gauss, is completely astonishing, not only for the result itself, but above all for the path taken to demonstrate this result. As we know, however, we mathematicians are good at generalizing things. We have talked about squares, triangles, and so nothing prevents us from generalizing to regular polygons! We say that a natural number k is n-gonal if with k units I can form a regular n-agon. In 1638, Pierre de Fermat, stated that every positive integer could be written as the sum of at most n triangular numbers. Fermat, as he usually did, did not demonstrate this fact. Only more than 150 years later, exactly in 1814, Cauchy managed to demonstrate Fermat’s conjecture. Research on additive number theory is very broad, just think that Goldbach, on June 7, 1742, sent a letter to Euler stating what is now called Goldbach’s conjecture: “If k ∈ ℕ with k≥6 then k=p+q+r for certain primes p,q and r”. Thanks to intense use of computers, this conjecture has been verified up to very large numbers (such as 10¹⁸), but a general proof has not yet been found! Some progress has been made, however: in 2014, H. Helfgott published the proof of what was called the weak Goldbach conjecture: “every odd number greater than or equal to 9 is the sum of three odd primes”.

Leave a comment